Advanced Concepts

The Layout process

Getting views to render with the right dimensions and positions requires a run of the layout process. When rendering, a recursive process runs through every view in the view hierarchy in two passes — a measure pass and a layout pass.

During the measure pass every view is measured to obtain its desired size. The following properties are considered during the measuring:

width,heightminWidth,minHeightvisibilitymarginTop,marginRight,marginBottom,marginLeft

During the layout pass every view is placed in a specific layout slot. The slot is determined by the result of the measure pass and the following properties:

marginTop,marginRight,marginBottom,marginLefthorizontalAlignment,verticalAlignment

The layout process is by nature an resource-intensive process and it's performance highly depends on the number views (and complexity).

TIP

Try to keep the view hierarchy as flat as possible by utilizing different Layout Containers rather than relying on excessive view nesting.

For example: don't treat <StackLayout> as a <div> — instead try to use a <GridLayout> with specific rows and columns to achieve the same result:

<StackLayout>

<StackLayout orientation="horizontal">

<SomeItem />

<SomeItem />

</StackLayout>

<StackLayout orientation="horizontal">

<!-- ... -->

</StackLayout>

</StackLayout>

<GridLayout rows="auto, auto" columns="auto, auto">

<SomeItem row="0" col="0" />

<SomeItem row="0" col="1" />

<!-- ... row="1" ... -->

</GridLayout>

One-offs are fine with the <StackLayout> approach, but building a whole app with the first approach will usually result in poor performance.

Custom Application and Activity

NativeScript provides a way to create custom android.app.Application and android.app.Activity implementations.

Extending the Android Application

Create a new TypeScript file in the root of your project folder - name it

application.android.tsorapplication.android.jsif you are using plain JS.Note

Note the *.android suffix - we want this file packaged for Android only.

Copy the following code for TypeScript file:

// the `JavaProxy` decorator specifies the package and the name for the native *.JAVA file generated.

@NativeClass()

@JavaProxy('org.myApp.Application')

class Application extends android.app.Application {

public onCreate(): void {

super.onCreate()

// At this point modules have already been initialized

// Enter custom initialization code here

}

public attachBaseContext(baseContext: android.content.Context) {

super.attachBaseContext(baseContext)

// This code enables MultiDex support for the application (if needed)

// androidx.multidex.MultiDex.install(this);

}

}

Copy the following code for the JavaScript file:

const superProto = android.app.Application.prototype

// the first parameter of the `extend` call defines the package and the name for the native *.JAVA file generated.

android.app.Application.extend('org.myApp.Application', {

onCreate: function () {

superProto.onCreate.call(this)

// At this point modules have already been initialized

// Enter custom initialization code here

},

attachBaseContext: function (base) {

superProto.attachBaseContext.call(this, base)

// This code enables MultiDex support for the application (if needed compile androidx.multidex:multidex)

// androidx.multidex.MultiDex.install(this);

}

})

- Modify the application entry within the AndroidManifest.xml file found in the

<application-name>/App_Resources/Android/folder:

<application

android:name="org.myApp.Application"

android:allowBackup="true"

android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher"

android:label="@string/app_name"

android:theme="@style/AppTheme" >

Note

This modification is required by the native platform; it tells Android that your custom Application class will be used as the main entry point of the application.

- In order to build the app, the extended Android application should be added to the webpack.config.js file.

const webpack = require('@nativescript/webpack')

module.exports = env => {

webpack.init(env)

webpack.chainWebpack(config => {

if (webpack.Utils.platform.getPlatformName() === 'android') {

// make sure the path to the applicatioon.android.(js|ts)

// is relative to the webpack.config.js

// you may need to use `./app/application.android if

// your app source is located inside the ./app folder.

config.entry('application').add('./application.android')

}

})

return webpack.resolveConfig()

}

The source code of application.android.ts is bundled separately as application.js file which is loaded from the native Application.java class on launch.

The bundle.js and vendor.js files are not loaded early enough in the application launch. That's why the logic in application.android.ts is needed to be bundled separately in order to be loaded as early as needed in the application lifecycle.

Note

This approach will not work if application.android.ts requires external modules.

Extending Android Activity

NativeScript Core ships with a default androidx.appcompat.app.AppCompatActivity implementation, that bootstraps the NativeScript application, without forcing users to declare their custom Activity in every project. In some cases you may need to implement a custom Android Activity. In this section we'll look at how to do that!

Create a new activity.android.ts or activity.android.js when using plain JS.

Note

Note the .android.(js|ts) suffix - we only want this file on Android.

A basic Activity looks as follows:

import {

Frame,

Application,

setActivityCallbacks,

AndroidActivityCallbacks

} from '@nativescript/core'

@NativeClass()

@JavaProxy('org.myApp.MainActivity')

class Activity extends androidx.appcompat.app.AppCompatActivity {

public isNativeScriptActivity

private _callbacks: AndroidActivityCallbacks

public onCreate(savedInstanceState: android.os.Bundle): void {

Application.android.init(this.getApplication())

// Set the isNativeScriptActivity in onCreate (as done in the original NativeScript activity code)

// The JS constructor might not be called because the activity is created from Android.

this.isNativeScriptActivity = true

if (!this._callbacks) {

setActivityCallbacks(this)

}

this._callbacks.onCreate(this, savedInstanceState, this.getIntent(), super.onCreate)

}

public onNewIntent(intent: android.content.Intent): void {

this._callbacks.onNewIntent(this, intent, super.setIntent, super.onNewIntent)

}

public onSaveInstanceState(outState: android.os.Bundle): void {

this._callbacks.onSaveInstanceState(this, outState, super.onSaveInstanceState)

}

public onStart(): void {

this._callbacks.onStart(this, super.onStart)

}

public onStop(): void {

this._callbacks.onStop(this, super.onStop)

}

public onDestroy(): void {

this._callbacks.onDestroy(this, super.onDestroy)

}

public onPostResume(): void {

this._callbacks.onPostResume(this, super.onPostResume)

}

public onBackPressed(): void {

this._callbacks.onBackPressed(this, super.onBackPressed)

}

public onRequestPermissionsResult(

requestCode: number,

permissions: Array<string>,

grantResults: Array<number>

): void {

this._callbacks.onRequestPermissionsResult(

this,

requestCode,

permissions,

grantResults,

undefined /*TODO: Enable if needed*/

)

}

public onActivityResult(

requestCode: number,

resultCode: number,

data: android.content.Intent

): void {

this._callbacks.onActivityResult(

this,

requestCode,

resultCode,

data,

super.onActivityResult

)

}

}

import { Frame, Application, setActivityCallbacks } from '@nativescript/core'

const superProto = androidx.appcompat.app.AppCompatActivity.prototype

androidx.appcompat.app.AppCompatActivity.extend('org.myApp.MainActivity', {

onCreate: function (savedInstanceState) {

// Used to make sure the App is inited in case onCreate is called before the rest of the framework

Application.android.init(this.getApplication())

// Set the isNativeScriptActivity in onCreate (as done in the original NativeScript activity code)

// The JS constructor might not be called because the activity is created from Android.

this.isNativeScriptActivity = true

if (!this._callbacks) {

setActivityCallbacks(this)

}

// Modules will take care of calling super.onCreate, do not call it here

this._callbacks.onCreate(

this,

savedInstanceState,

this.getIntent(),

superProto.onCreate

)

// Add custom initialization logic here

},

onNewIntent: function (intent) {

this._callbacks.onNewIntent(

this,

intent,

superProto.setIntent,

superProto.onNewIntent

)

},

onSaveInstanceState: function (outState) {

this._callbacks.onSaveInstanceState(this, outState, superProto.onSaveInstanceState)

},

onStart: function () {

this._callbacks.onStart(this, superProto.onStart)

},

onStop: function () {

this._callbacks.onStop(this, superProto.onStop)

},

onDestroy: function () {

this._callbacks.onDestroy(this, superProto.onDestroy)

},

onPostResume: function () {

this._callbacks.onPostResume(this, superProto.onPostResume)

},

onBackPressed: function () {

this._callbacks.onBackPressed(this, superProto.onBackPressed)

},

onRequestPermissionsResult: function (requestCode, permissions, grantResults) {

this._callbacks.onRequestPermissionsResult(

this,

requestCode,

permissions,

grantResults,

undefined

)

},

onActivityResult: function (requestCode, resultCode, data) {

this._callbacks.onActivityResult(

this,

requestCode,

resultCode,

data,

superProto.onActivityResult

)

}

/* Add any other events you need to capture */

})

Note

The this._callbacks property is automatically assigned to your extended class by the frame.setActivityCallbacks method. It implements the AndroidActivityCallbacks interface and allows the core modules to get notified for important Activity events. It is important to use these callbacks, as many parts of NativeScript rely on them!

Next, modify the activity in App_Resources/Android/src/main/AndroidManifest.xml

<activity

android:name="org.myApp.MainActivity"

android:label="@string/title_activity_kimera"

android:configChanges="keyboardHidden|orientation|screenSize">

To include the new Activity in the build, it has to be added to the webpack compilation by editing the webpack.config.js:

const webpack = require('@nativescript/webpack')

module.exports = env => {

env.appComponents = (env.appComponents || []).concat(['./src/activity.android'])

webpack.init(env)

return webpack.resolveConfig()

}

Adding ObjectiveC/Swift Code

For the Objective-C/Swift symbols to be accessible by the Nativescript runtimes the following criteria should be met:

1) They need to be compiled and linked

2) Metadata needs to be generated for them

The first task is done by the NativeScript CLI by adding the source files to the generated .xcodeproj. For the second one the Metadata Generator needs to find a module.modulemap of the compiled modules.

Note

For .swift files module.modulemap is not required.

In order to satisfy the above constraints the developer has to:

1) Place the source files in App_Resources/iOS/src/

2) Create a modulemap for the Objective-C files

Note

Swift classes need to be accessible from the Objective-C runtime in order to be used from NativeScript. This can be done by using the @objc attribute or by inheriting NSObject.

For a detailed walkthrough on how to use native iOS source code in NativeScript here.

Objective C Example

A minimal example for adding native Objective C source code to your NativeScript application:

- Create ExampleCrypto.m file with the following content:

// import required header files

#import <CommonCrypto/CommonDigest.h>

#import <CommonCrypto/CommonHMAC.h>

#import "ExampleCrypto.h"

@implementation ExampleCrypto

+ (NSString *)generateHMACWithApiKey:(NSString *) apiKey andApiSecret:(NSString *) apiSecret {

NSString *hmacData = [NSString stringWithFormat:@"%@%@%@%@%@",apiKey];

// Make sure the HMAC hash is in hex

unsigned char outputHMAC[CC_SHA256_DIGEST_LENGTH];

const char* keyChar = [apiSecret cStringUsingEncoding:NSUTF8StringEncoding];

const char* dataChar = [hmacData cStringUsingEncoding:NSUTF8StringEncoding];

CCHmac(kCCHmacAlgSHA256, keyChar, strlen(keyChar), dataChar, strlen(dataChar), outputHMAC);

NSData* hmacHash = [[NSData alloc] initWithBytes:outputHMAC length:sizeof(outputHMAC)];

NSString* hmacHashHexString = [[hmacHash description] stringByReplacingOccurrencesOfString:@" " withString:@""];

// Authorization : base64 of hmac hash -->

NSString* authorization = [[hmacHashHexString dataUsingEncoding:NSUTF8StringEncoding] base64EncodedStringWithOptions:0];

return authorization;

}

@end

- Create ExampleCrypto.h file with the following content:

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

@interface ExampleCrypto : NSObject

+ (NSString *)generateHMACWithApiKey:(NSString *)apiKey andApiSecret:(NSString *)apiSecret;

@end

- Create the module.modulemap file with the following content:

module ExampleCrypto {

header "ExampleCrypto.h"

export *

}

- Call the static method from the ObjectiveC source code just added somewhere in your application.

function generateNativeIOSHMAC() {

// This if check ensures the following code is only executed on iOS.

if (global.isIOS) {

const apiKey = '9292skksd88172alekdd782939ssa'

const apiSecret = 'f82828282828f992f'

const base64encryptedKey = ExampleCrypto.generateHMACWithApiKeyandApiSecret(

apiKey,

apiSecret

)

console.log('base64encryptedKey', base64encryptedKey)

}

}

- Build your NativeScript application by running the following and you should see the base64encryptedKey print in your terminal.

ns clean

ns run ios --no-hmr

Marshalling

iOS Marshalling

NativeScript for iOS handles the conversion between JavaScript and Objective-C data types implicitly. However, the rules that govern this conversion need to take into account the differences between JavaScript and Objective-C. NativeScript tries to translate idioms between languages, but there are quirks and features in both that are hard to reconcile. The following is a thorough but not exhaustive list of rules and exceptions NativeScript abides by when exposing Objective-C APIs in JavaScript.

Objective-C Classes and Objects

The most common data type in Objective-C by far is the class. Classes can have instance or static methods, and properties which are always instance. NativeScript exposes an Objective-C class and its members as a JavaScript constructor function with an associated prototype according to the prototypal inheritance model. This means that each static method on an Objective-C class becomes a function on its JavaScript constructor function, each instance method becomes a function on the JavaScript prototype, and each property becomes a property descriptor on the same prototype. Every JavaScript constructor function created to expose an Objective-C class is arranged in a prototype chain that mirrors the class hierarchy in Objective-C: if NSMutableArray extends NSArray, which in turn extends NSObject in Objective-C, then in JavaScript the prototype of the NSObject constructor function is the prototype of NSArray, which in turn is the prototype of NSMutableArray.

To illustrate:

@interface NSArray : NSObject

+ (instancetype)arrayWithArray:(NSArray *)anArray;

- (id)objectAtIndex:(NSUInteger)index;

@property (readonly) NSUInteger count;

@end

var NSArray = {

__proto__: NSObject,

arrayWithArray: function () {

[native code]

}

}

NSArray.prototype = {

__proto__: NSObject.prototype,

constructor: NSArray,

objectAtIndex: function () {

[native code]

},

get count() {

[native code]

}

}

Instances of Objective-C classes exist in JavaScript as special "wrapper" exotic objects - they keep track of and reference native objects, as well as manage their memory. When a native API returns an Objective-C object, NativeScript constructs such a wrapper for it in case one doesn't already exist. Wrappers have a prototype just like regular JavaScript objects. This prototype is the same as the prototype of the JavaScript constructor function that exposes the class the native object is an instance of. In essence:

const tableViewController = new UITableViewController() // returns a wrapper around a UITableViewController instance

Object.getPrototypeOf(tableViewController) === UITableViewController.prototype // returns true

There is only one JavaScript wrapper around an Objective-C object, always. This means that Objective-C wrappers maintain JavaScript identity equality:

tableViewController.tableView === tableViewController.tableView

Calling native APIs that expect Objective-C classes or objects is easy - just pass the JavaScript constructor function for the class, or the wrapper for the object.

If an API is declared as accepting a Class in Objective-C, the argument in JavaScript is the constructor function:

NSString *className = NSStringFromClass([NSArray class]);

const className = NSStringFromClass(NSArray)

Conversely, if an API is declared as accepting an instance of a specific class such as NSDate, the argument is a wrapper around an object inheriting from that class.

NSDateFormatter *formatter = [[NSDateFormatter alloc] init];

NSDate *date = [NSDate date];

NSString *formattedDate = [formatter stringFromDate:date];

const formatter = new NSDateFormatter()

const date = NSDate.date()

const formattedDate = formatter.stringFromDate(date)

An API expecting the id data type in Objective-C means it will any accept Objective-C class or object in JavaScript.

NSMutableArray *array = [[NSMutableArray alloc] init];

Class buttonClass = [UIButton class];

UIButton *button = [[buttonClass alloc] init];

[array setObject:buttonClass atIndex:0];

[array setObject:button atIndex:1];

const array = new NSMutableArray()

const buttonClass = UIButton

const button = new buttonClass()

array.setObjectAtIndex(buttonClass, 0)

array.setObjectAtIndex(button, 1)

Converting JavaScript array to CGFloat array

In the below-given code sample, you can see, how to convert a JavaScript array to a CGFloat array. In the tabs, you will find the Objective-C code for a function accepting a CGFloat array as an argument and the JavaScript code for calling this native function.

const CGFloatArray = interop.sizeof(interop.types.id) == 4 ? Float32Array : Float64Array

const jsArray = [4.5, 0, 1e-5, -1242e10, -4.5, 34, -34, -1e-6]

FloatArraySample.dumpFloats(CGFloatArray.from(jsArray), jsArray.length)

@interface FloatArraySample

+ (void)dumpFloats:(CGFloat*) arr withCount:(int)cnt;

@end

@implementation TNSBaseInterface

+ (void)dumpFloats:(CGFloat*) arr withCount:(int)cnt {

for(int i = 0; i < cnt; i++) {

NSLog(@"arr[%d] = %f", i, arr[i]);

}

}

@end

Note

Keep in mind that CGFloat is architecture dependent. On 32-bit devices, we need to use Float32Array and Float64Array -- on 64-bit ones. A straightforward way to verify the device/emulator architecture is to check the pointer size via interop.sizeof(interop.types.id). The return value for the pointer size will be 4 bytes for 32-bit architectures and 8 bytes - for 64-bit ones. For further info, check out CGFloat's documentation.

Primitive Exceptions

NativeScript considers instances of NSNull, NSNumber, NSString and NSDate to be "primitives". This means that instances of these classes won't be exposed in JavaScript via a wrapper exotic object, instead they will be converted to the equivalent JavaScript data type: NSNull becomes null, NSNumber becomes number or boolean, NSString becomes string and NSDate becomes Date. The exception to this are the methods on those classes declared as returning instancetype - init methods and factory methods. This means that a call to NSString.stringWithString whose return type in Objective-C is instancetype will return a wrapper around an NSString instance, rather than a JavaScript string. This applies for all methods on NSNull, NSNumber, NSString and NSDate returning instancetype.

On the other hand, any API that expects a NSNull, NSNumber, NSString or NSDate instance in Objective-C can be called either with a wrapper object or a JavaScript value - null, number or boolean, string or Date, in JavaScript. The conversion is automatically handled by NativeScript.

More information on how NativeScript deals with Objective-C classes is available here.

Objective-C Protocols

Protocols in Objective-C are like interfaces in other languages - they are blueprints of what members a class should contain, a sort of an API contract. Protocols are exposed as empty objects in JavaScript. Protocols are usually only referenced when subclassing an Objective-C class or when checking whether an object or class conforms to a protocol.

BOOL isCopying = [NSArray conformsToProtocol:@protocol(NSCopying)];

const isCopying = NSArray.conformsToProtocol(NSCopying)

Objective-C Selectors

In Objective-C SEL is a data type that represents the name of a method of an Objective-C class. NativeScript exposes this data type as a JavaScript string. Whenever an API expects a selector value in Objective-C, it's JavaScript projection will expect a string with the method name.

NSMutableString *aString = [[NSMutableString alloc] init];

BOOL hasAppend = [aString respondsToSelector:@selector(appendString:)];

const aString = NSMutableString.alloc().init()

const hasAppend = aString.respondsToSelector('appendString:')

Objective-C Blocks

Objective-C blocks are anonymous functions in Objective-C. They can be closures, just like JavaScript functions, and are often used as callbacks. NativeScript implicitly exposes an Objective-C block as a JavaScript function. Any API that accepts a block in Objective-C accepts a JavaScript function when called in JavaScript:

NSURL *url = [NSURL URLWithString:@"http://example.com"];

NSURLRequest *request = [NSURLRequest requestWithURL:url];

[NSURLConnection sendAsynchronousRequest:request queue:nil completionHandler:^(NSURLResponse *response, NSData *data, NSError *connectionError) {

NSLog(@"request complete");

}];

const url = NSURL.URLWithString('http://example.com')

const request = NSURLRequest.requestWithURL(url)

NSURLConnection.sendAsynchronousRequestQueueCompletionHandler(

request,

null,

(response, data, connectionError) => {

console.log('request complete')

}

)

Blocks in Objective-C, especially blocks that are closures, need to be properly retained and released in order to not leak memory. NativeScript does this automatically - a block exposed as a JavaScript function is released as soon as the function is garbage collected. A JavaScript function implicitly converted to a block will not be garbage collected as long the block is not released.

CoreFoundation Objects

iOS contains both an Objective-C standard library (the Foundation framework) and a pure C standard library (Core Foundation). Core Foundation is modeled after Foundation to a great extent and implements a limited object model. Data types such as CFDictionaryRef and CFBundleRef are Core Foundation objects. Core Foundation objects are retained and released just like Objective-C objects, using the CFRetain and CFRelease functions. NativeScript implements automatic memory management for functions that are annotated as returning a retained Core Foundation object. For those that are not annotated, NativeScript returns an Unmanaged type that wraps the Core Foundation instance. This makes you partially responsible for keeping the instance allive. You could either

- Call takeRetainedValue() which would return managed reference to the wrapped instance, decrementing the reference count while doing so

- Call takeUnretainedValue() which would return managed reference to the wrapped instance without decrementing the reference count

Toll-free Bridging

Core Foundation has the concept of Toll-free bridged types - data types which can be used interchangeably with their Objective-C counterparts. When dealing with a toll-free bridged type NativeScript always treats it as its Objective-C counterpart. Core Foundation objects on the toll-free bridged types list are exposed as if they were instances of the equivalent Objective-C class. This means that a CFDictionaryRef value in JavaScript has the same methods on its prototype as if it were a NSDictionary object. Unlike regular Core Foundation objects, toll-free bridged types are automatically memory managed by NativeScript, so there is no need to retain or release them using CFRetain and CFRelease.

Null Values

Objective-C has three null values - NULL, Nil and nil. NULL means a regular C pointer to zero, Nil is a NULL pointer to an Objective-C class, and nil is a NULL pointer to an Objective-C object. They are implicitly converted to null in JavaScript. When calling a native API with a null argument NativeScript converts the JavaScript null value to a C pointer to zero. Some APIs require their arguments to not be pointers to zero - invoking them with null in JavaScript can potentially crash the application without a chance to recover.

Numeric Types

Integer and floating point data types in Objective-C are converted to JavaScript numbers. This includes types such as char, int, long, float, double, NSInteger and their unsigned variants. However, integer values larger than ±253 will lose their precision because the JavaScript number type is limited in size to 53-bit integers.

Struct Types

NativeScript exposes Objective-C structures as JavaScript objects. The properties on such an object are the same as the fields on the structure it exposes. APIs that expect a struct type in Objective-C can be called with a JavaScript object with the same shape as the structure:

CGRect rect = {

.origin = {

.x = 0,

.y = 0

},

.size = {

.width = 100,

.height = 100

}

};

UIView *view = [[UIView alloc] initWithFrame:rect];

const rect = {

origin: {

x: 0,

y: 0

},

size: {

width: 100,

height: 100

}

}

const view = UIView.alloc().initWithFrame(rect)

More information on how NativeScript deals with structures is available here.

NSError ** marshalling

Native to JavaScript

@interface NSFileManager : NSObject

+ (NSFileManager *)defaultManager;

- (NSArray *)contentsOfDirectoryAtPath:(NSString *)path error:(NSError **)error;

@end

We can use this method from JavaScript in the following way:

const fileManager = NSFileManager.defaultManager

const bundlePath = NSBundle.mainBundle.bundlePath

console.log(fileManager.contentsOfDirectoryAtPathError(bundlePath, null))

If we want to check the error using out parameters:

const errorRef = new interop.Reference()

fileManager.contentsOfDirectoryAtPathError('/not-existing-path', errorRef)

console.log(errorRef.value) // NSError: "The folder '/not-existing-path' doesn't exist."

Or we can skip passing the last NSError ** out parameter and a JavaScript error will be thrown if the NSError ** is set from native:

try {

fileManager.contentsOfDirectoryAtPathError('/not-existing-path')

} catch (e) {

console.log(e) // NSError: "The folder '/not-existing-path' doesn't exist."

}

JavaScript to Native

When overriding a method having NSError ** out parameter in the end any thrown JavaScript error will be wrapped and set to the NSError ** argument (if given).

Pointer Types

Languages in the C family have the notion of a pointer data type. A pointer is a value that points to another value, or, more accurately, to the location of that value in memory. JavaScript has no notion of pointers, but the pointer data type is used throughout the iOS SDK. To overcome this, NativeScript introduces the Reference object. References are special objects which allow JavaScript to reason about and access pointer values. Consider this example:

NSFileManager *fileManager = [NSFileManager defaultManager];

BOOL isDirectory;

BOOL exists = [fileManager fileExistsAtPath:@"/var/log" isDirectory:&isDirectory];

if (isDirectory) {

NSLog(@"The path is actually a directory");

}

This snippet calls the fileExistsAtPath:isDirectory method of the NSFileManager class. This method accepts a NSString as its first argument and a pointer to a boolean value as its second argument. During its execution the method will use the pointer to update the boolean value. This means it will directly change the value of isDirectory. The same code can be written as follows:

const fileManager = NSFileManager.defaultManager

const isDirectory = new interop.Reference()

const exists = fileManager.fileExistsAtPathIsDirectory('/var/log', isDirectory)

if (isDirectory.value) {

console.log('The path is actually a directory')

}

Android Marshalling

Data Conversion

Being two different worlds, Java/Kotlin and JavaScript use different data types. For example java.lang.String is not the same as the JavaScript's String. The NativeScript Runtime provides implicit type conversion that projects types and values from JavaScript to Java and vice-versa. The Kotlin support in the runtime is similar and data conversion is described in the articles JavaScript to Kotlin and Kotlin to JavaScript There are several corner cases - namely with different method overloads, where an explicit input is required to call the desired method but these cases are not common and a typical application will seldom (if ever) need such explicit conversion.

JavaScript to Java Conversion

The article lists the available types in JavaScript and how they are projected to Java.

String

JavaScript String maps to java.lang.String:

var context = ...;

var button = new android.widget.Button(context);

var text = "My Button"; // JavaScript string

button.setText(text); // text is converted to java.lang.String

Boolean

JavaScript Boolean maps to Java primitive boolean.

var context = ...;

var button = new android.widget.Button(context);

var enabled = false; // JavaScript Boolean

button.setEnabled(enabled); // enabled is converted to Java primitive boolean

Undefined & Null

JavaScript Undefined & Null maps to Java null literal (or null pointer).

var context = ...;

var button = new android.widget.Button(context);

button.setOnClickListener(undefined); // the Java call will be made using the null keyword

Number

Java has several primitive numeric types while JavaScript has the Number type only. Additionally, unlike JavaScript, Java is a language that supports Method Overloading, which makes the numeric conversion more complex. Consider the following Java class:

class MyObject extends java.lang.Object {

public void myMethod(byte value){

}

public void myMethod(short value){

}

public void myMethod(int value){

}

public void myMethod(long value){

}

public void myMethod(float value){

}

public void myMethod(double value){

}

}

The following logic applies when calling myMethod on a myObject instance from JavaScript:

var myObject = new MyObject()

- Implicit integer conversion:

myObject.myMethod(10) // myMethod(int) will be called.

Note

If there is no myMethod(int) implementation, the Runtime will try to choose the best possible overload with least conversion loss. If no such method is found an exception will be raised.

- Implicit floating-point conversion:

myObject.myMethod(10.5) // myMethod(double) will be called.

Note

If there is no myMethod(double) implementation, the Runtime will try to choose the best possible overload with least conversion loss. If no such method is found an exception will be raised.

Explicitly call an overload:

To enable developers call a specific method overload, the Runtime exposes the following functions directly in the global context:* byte(number) → Java primitive byte > The number value will be truncated and only its first byte of the whole part will be used. * short(number) → Java primitive short > The number value will be truncated and only its first 2 bytes of the whole part will be used. * float(number) → Java primitive float > The number value will be converted (with a possible precision loss) to a 2^32 floating-point value. * long(number) → Java primitive long (in case the number literal fits JavaScript 2^53 limit) > The number value's whole part will be taken only. * long("number") → Java primitive long (in case the number literal doesn't fit JavaScript 2^53 limit)

myObject.myMethod(byte(10)) // will call myMethod(byte)

myObject.myMethod(short(10)) // will call myMethod(short)

myObject.myMethod(float(10)) // will call myMethod(float)

myObject.myMethod(long(10)) // will call myMethod(long)

myObject.myMethod(long('123456')) // will convert "123456" to Java long and will call myMethod(long)

Note

When an explicit cast function is called and there is no such implementation found, the Runtime will directly fail, without trying to find a matching overload.

Array

A JavaScript Array is implicitly converted to a Java Array, using the above described rules for type conversion of the array's elements. For example:

class MyObject extends java.lang.Object {

public void myMethod(java.lang.String[] items){

}

}

var items = ['One', 'Two', 'Three']

var myObject = new MyObject()

myObject.myMethod(items) // will convert to Java array of java.lang.String objects

Javascript to Kotlin Conversion

The article lists the available types in JavaScript and how they are projected to Kotlin.

String

JavaScript String maps to kotlin.String:

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithStringProperty()

var text = 'My Button' // JavaScript string

kotlinClass.setStringProperty(text) // text is converted to kotlin.String

Boolean

JavaScript Boolean maps to Kotlin class Boolean.

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithBooleanProperty()

var enabled = false // JavaScript Boolean

kotlinClass.setBooleanProperty(enabled) // enabled is converted to Kotlin Boolean

Undefined & Null

JavaScript Undefined & Null maps to Kotlin null literal (or null pointer).

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithNullableParameter(undefined) // the Kotlin call will be made using the null keyword

Number

Kotlin has several numeric types while JavaScript has the Number type only. Additionally, unlike JavaScript, Kotlin is a language that supports Method Overloading, which makes the numeric conversion more complex. Consider the following Java class:

class MyObject : Any() {

fun myMethod(value: Byte) {}

fun myMethod(value: Short) {}

fun myMethod(value: Int) {}

fun myMethod(value: Long) {}

fun myMethod(value: Float) {}

fun myMethod(value: Double) {}

}

The following logic applies when calling myMethod on a myObject instance from JavaScript:

var myObject = new MyObject()

- Implicit integer conversion:

myObject.myMethod(10) // myMethod(Int) will be called.

Note

If there is no myMethod(Int) implementation, the Runtime will try to choose the best possible overload with least conversion loss. If no such method is found an exception will be raised.

- Implicit floating-point conversion:

myObject.myMethod(10.5) // myMethod(Double) will be called.

Note

If there is no myMethod(Double) implementation, the Runtime will try to choose the best possible overload with least conversion loss. If no such method is found an exception will be raised.

Explicitly call an overload:

To enable developers call a specific method overload, the Runtime exposes the following functions directly in the global context:* byte(number) → Kotlin Byte >The number value will be truncated and only its first byte of the whole part will be used. * short(number) → Kotlin Short >The number value will be truncated and only its first 2 bytes of the whole part will be used. * float(number) → Kotlin Float >The number value will be converted (with a possible precision loss) to a 2^32 floating-point value. * long(number) → Kotlin Long (in case the number literal fits JavaScript 2^53 limit) >The number value's whole part will be taken only. * long("number") → Kotlin Long (in case the number literal doesn't fit JavaScript 2^53 limit)

myObject.myMethod(byte(10)) // will call myMethod(Byte)

myObject.myMethod(short(10)) // will call myMethod(Short)

myObject.myMethod(float(10)) // will call myMethod(Float)

myObject.myMethod(long(10)) // will call myMethod(Long)

myObject.myMethod(long('123456')) // will convert "123456" to Kotlin Long and will call myMethod(Long)

Note

When an explicit cast function is called and there is no such implementation found, the Runtime will directly fail, without trying to find a matching overload.

Array

A JavaScript Array is implicitly converted to a Kotlin Array, using the above described rules for type conversion of the array's elements. For example:

class MyObject : Any() {

fun myMethod(items: Array<String>) {}

}

var items = ['One', 'Two', 'Three']

var myObject = new MyObject()

myObject.myMethod(items) // will convert to Java array of java.lang.String objects

Java to Javascript Conversion

The article lists the available types in Java and how they are projected to JavaScript.

String & Character

Both java.lang.String and java.lang.Character types are projected as JavaScript String:

var file = new java.io.File('/path/to/file')

var path = file.getPath() // returns java.lang.String, converted to JS String

Boolean & Primitive boolean

Both the primitive boolean and reference java.lang.Boolean types are projected as JavaScript Boolean:

var context = ...

var button = new android.widget.Button(context);

var enabled = button.isEnabled(); // returns primitive boolean, converted to JS Boolean

Byte & Primitive byte

Both the primitive byte and reference java.lang.Byte types are projected as JavaScript Number:

var byte = new java.lang.Byte('1')

var jsByteValue = byte.byteValue() // returns primitive byte, converted to Number

Short & Primitive short

Both the primitive short and reference java.lang.Short types are projected as JavaScript Number:

var short = new java.lang.Short('1')

var jsShortValue = short.shortValue() // returns primitive short, converted to Number

Integer & Primitive int

Both the primitive int and reference java.lang.Integer types are projected as JavaScript Number:

var int = new java.lang.Integer('1')

var jsIntValue = int.intValue() // returns primitive int, converted to Number

Float & Primitive float

Both the primitive float and reference java.lang.Float types are projected as JavaScript Number:

var float = new java.lang.Float('1.5')

var jsFloatValue = float.floatValue() // returns primitive float, converted to Number

Double & Primitive double

Both the primitive double and reference java.lang.Double types are projected as JavaScript Number:

var double = new java.lang.Double('1.5')

var jsDoubleValue = double.doubleValue() // returns primitive double, converted to Number

Long & Primitive long

java.lang.Long and its primitive equivalent are special types which are projected to JavaScript by applying the following rules:

- If the value is in the interval (-2^53, 2^53) then it is converted to Number

- Else a special object with the following characteristics is created:

- Has Number.NaN set as a prototype

- Has value property set to the string representation of the Java long value

- Its valueOf() method returns NaN

- Its toString() method returns the string representation of the Java long value

public class TestClass {

public long getLongNumber54Bits(){

return 1 << 54;

}

public long getLongNumber53Bits(){

return 1 << 53;

}

}

var testClass = new TestClass()

var jsNumber = testClass.getLongNumber53Bits() // result is JavaScript Number

var specialObject = testClass.getLongNumber54Bits() // result is the special object described above

Array

Array in Java is a special java.lang.Object that have an implicit Class associated. A Java Array is projected to JavaScript as a special JavaScript proxy object with the following characteristics:

- Has length property

- Has registered indexed getter and setter callbacks, which:

- If the array contains elements of type convertible to a JavaScript type, then accessing the i-th element will return a converted type

- If the array contains elements of type non-convertible to JavaScript, then accessing the i-th element will return a proxy object over the Java/Android type (see Accessing APIs)

var directory = new java.io.File('path/to/myDir')

var files = directory.listFiles() // files is a special object as described above

var singleFile = files[0] // the indexed getter callback is triggered and a proxy object over the java.io.File is returned

Note

A Java Array is intentionally not converted to a JavaScript Array for the sake of performance, especially when it comes to large arrays.

Array of Objects

Occasionally you have to create Java arrays from JavaScript. For this scenario we added method create to built-in JavaScript Array object. Here are some examples how to use Array.create method:

// the following statement is equivalent to byte[] byteArr = new byte[10];

var byteArr = Array.create('byte', 10)

// the following statement is equivalent to String[] stringArr = new String[10];

var stringArr = Array.create(java.lang.String, 10)

Here is the full specification for Array.create method

Array.create(elementClassName, length)

Array.create(javaClassCtorFunction, length)

The first signature accepts string for elementClassName. This option is useful when you have to create Java array of primitive types (e.g. char, boolean, byte, short, int, long, float and double). It is also useful when you have to create Java jagged arrays. For this scenario elementClassName must be the standard JNI class notation. Here are some examples:

// equivalent to int[][] jaggedIntArray2 = new int[10][];

var jaggedIntArray2 = Array.create('[I', 10)

// equivalent to boolean[][][] jaggedBooleanArray3 = new boolean[10][][];

var jaggedBooleanArray3 = Array.create('[[Z', 10)

// equivalent to Object[][][][] jaggedObjectArray4 = new Object[10][][][];

var jaggedObjectArray4 = Array.create('[[[Ljava.lang.Object;', 10)

The second signature uses javaClassCtorFunction which must the JavaScript constructor function for a given Java type. Here are some examples:

// equivalent to String[] stringArr = new String[10];

var stringArr = Array.create(java.lang.String, 10)

// equivalent to Object[] objectArr = new Object[10];

var objectArr = Array.create(java.lang.Object, 10)

Array of Primitive Types

The automatic marshalling works only for cases with arrays of objects. In cases where you have a method that takes an array of primitive types, you need to convert it as follows:

public static void myMethod(int[] someParam)

Then yoy need to invoke it as follows:

let arr = Array.create('int', 3)

arr[0] = 1

arr[1] = 2

arr[2] = 3

SomeObject.myMethod(arr) // assuming the method is accepting an array of primitive types

However there are some other helpful classes we can use to create a few other arrays of primitive types

const byteArray = java.nio.ByteBuffer.wrap([1]).array()

const shortArray = java.nio.ShortBuffer.wrap([1]).array()

const intArray = java.nio.IntBuffer.wrap([1]).array()

const longArray = java.nio.LongBuffer.wrap([1]).array()

const floatArray = java.nio.FloatBuffer.wrap([1]).array()

const doubleArray = java.nio.DoubleBuffer.wrap([1]).array()

Two-Dimensional Arrays of Primitive Types

The above scenario gets more tricky with two-dimensional arrays. Consider a Java method that accepts as an argument a two-dimensional array:

public static void myMethod(java.lang.Integer[][] someParam)

The marshalled JavaScript code will look like this:

let arr = Array.create('[Ljava.lang.Integer;', 2)

let elements = Array.create('java.lang.Integer', 3)

elements[0] = new java.lang.Integer(1)

elements[1] = new java.lang.Integer(2)

elements[2] = new java.lang.Integer(3)

arr[0] = elements

SomeObject.myMethod(arr) // assuming the method is accepting a two-dimensional array of primitive types

Null

The Java null literal (or null pointer) is projected to JavaScript Null:

var context = ...

var button = new android.widget.Button(context);

var background = button.getBackground(); // if there is no background drawable method will return JS null

Android Types

All Android-declared types are projected to JavaScript using the Package and Class proxies as described in Accessing APIs

Kotlin to Javascript Conversion

The article lists the available types in Kotlin and how they are projected to JavaScript.

Keep in mind that some of Kotlin's fundamental types are translated to a Java type by the Kotlin compiler when targeting Android or the JVM. Those types are the following:

| Kotlin non-nullable type | Java type | Kotlin nullable type | Java type |

|---|---|---|---|

| kotlin.Any | java.lang.Object | kotlin.Any? | java.lang.Object |

| kotlin.String | java.lang.String | kotlin.String? | java.lang.String |

| kotlin.Char | char | kotlin.Char? | java.lang.Character |

| kotlin.Boolean | boolean | kotlin.Boolean? | java.lang.Boolean |

| kotlin.Byte | byte | kotlin.Byte? | java.lang.Byte |

| kotlin.Short | short | kotlin.Short? | java.lang.Short |

| kotlin.Int | int | kotlin.Int? | java.lang.Integer |

| kotlin.Long | long | kotlin.Long? | java.lang.Long |

| kotlin.Float | float | kotlin.Float? | java.lang.Float |

Although the conversion of Kotlin types in NativeScript is quite the same as the Java conversion, let's take a look at some examples.

String & Character

Both kotlin.String and kotlin.Char types are projected as JavaScript String:

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithStringAndCharProperty()

var str1 = kotlinClass.getStringProperty() // returns kotlin.String, converted to JS String

var str2 = kotlinClass.getCharProperty() // returns kotlin.Char, converted to JS String

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithStringAndCharProperty {

val stringProperty: String = "string property"

val charProperty: Char = 'c'

}

Boolean

Kotlin's boolean type kotlin.Boolean is projected as JavaScript Boolean:

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithBooleanProperty()

var enabled = kotlinClass.getBooleanProperty() // returns Kotlin Boolean, converted to JS Boolean

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithBooleanProperty {

val booleanProperty: Boolean = false

}

Byte

Kotlin's byte type kotlin.Byte is projected as JavaScript Number:

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithByteProperty()

var jsByteValue = kotlinClass.getByteProperty() // returns Kotlin Byte, converted to Number

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithByteProperty {

val byteProperty: Byte = 42

}

Short

Kotlin's short type kotlin.Short is projected as JavaScript Number:

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithShortProperty()

var jsShortValue = kotlinClass.getShortProperty() // returns Kotlin Short, converted to Number

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithShortProperty {

val shortProperty: Short = 42

}

Integer

Kotlin's integer type kotlin.Int is projected as JavaScript Number:

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithIntProperty()

var jsIntValue = kotlinClass.getIntProperty() // returns Kotlin Int, converted to Number

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithIntProperty {

val intProperty: Int = 42

}

Float

Kotlin's float type kotlin.Float is projected as JavaScript Number:

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithFloatProperty()

var jsFloatValue = kotlinClass.getFloatProperty() // returns Kotlin Float, converted to Number

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithFloatProperty {

val floatProperty: Float = 42.0f

}

Double

Kotlin's double type kotlin.Double is projected as JavaScript Number:

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithDoubleProperty()

var jsDoubleValue = kotlinClass.getDoubleProperty() // returns Kotlin double, converted to Number

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithDoubleProperty {

val doubleProperty: Double = 42.0

}

Long

Kotlin's long type kotlin.Long is a special type which is projected to JavaScript by applying the following rules:

- If the value is in the interval (-2^53, 2^53) then it is converted to Number

- Else a special object with the following characteristics is created:

- Has Number.NaN set as a prototype

- Has value property set to the string representation of the Kotlin long value

- Its valueOf() method returns NaN

- Its toString() method returns the string representation of the Kotlin long value

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithLongProperties {

val longNumber54Bits: Long

get() = (1 shl 54).toLong()

val longNumber53Bits: Long

get() = (1 shl 53).toLong()

}

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithLongProperties()

var jsNumber = kotlinClass.getLongNumber53Bits() // result is JavaScript Number

var specialObject = kotlinClass.getLongNumber54Bits() // result is the special object described above

Array

Array in Kotlin is a special object that has an implicit Class associated. A Kotlin Array is projected to JavaScript as a special JavaScript proxy object with the following characteristics:

- Has length property

- Has registered indexed getter and setter callbacks, which:

- If the array contains elements of type convertible to a JavaScript type, then accessing the n-th element will return a converted type

- If the array contains elements of type non-convertible to JavaScript, then accessing the n-th element will return a proxy object over the Kotlin type (see Accessing APIs)

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithStringArrayProperty()

var kotlinArray = kotlinClass.getStringArrayProperty() // kotlinArray is a special object as described above

var firstStringElement = kotlinArray[0] // the indexed getter callback is triggered and the kotlin.String is returned as a JS string

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithStringArrayProperty {

val stringArrayProperty: Array<String> = arrayOf("element1", "element2", "element3")

}

Note

A Kotlin Array is intentionally not converted to a JavaScript Array for the sake of performance, especially when it comes to large arrays.

Creating arrays

Occasionally you have to create Kotlin arrays from JavaScript. Because of the translation of the fundamental Kotlin types to Java types in Android, creating Kotlin array could be done the same way Java arrays are created. This is described in Java to JavaScript

Null

The Kotlin null literal (or null pointer) is projected to JavaScript Null:

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithNullableProperty()

var nullableValue = kotlinClass.getNullableProperty() // if there is no value, the method will return JS null

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithNullableProperty() {

val nullableProperty: Any? = null

}

Kotlin Types

All Kotlin types are projected to JavaScript using the Package and Class proxies as described in Accessing APIs

Kotlin Companion objects

Kotlin's companion objects could be accessed in JavaScript the same way they can be accessed in Java - by accessing the Companion field:

var companion = com.example.KotlinClassWithCompanion.Companion

var data = companion.getDataFromCompanion()

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithCompanion {

companion object {

fun getDataFromCompanion() = "some data"

}

}

Kotlin Object

Kotlin's objects could be accessed in JavaScript the same way they can be accessed in Java - by accessing the INSTANCE field:

var objectInstance = com.example.KotlinObject.INSTANCE

var data = objectInstance.getDataFromObject()

package com.example

object KotlinObject {

fun getDataFromObject() = "some data"

}

Accessing Kotlin properties

Kotlin's properties could be accessed in JavaScript the same way they can be accessed in Java - by using their compiler-generated get/set methods. Non-boolean Kotlin properties could be used in NativeScript applications as JS fields as well.

var kotlinClass = new com.example.KotlinClassWithStringProperty()

var propertyValue = kotlinClass.getStringPropert()

kotlinClass.setStringProperty('example')

propertyValue = kotlinClass.stringProperty

kotlinClass.stringProperty = 'second example'

package com.example

class KotlinClassWithStringProperty(var stringProperty: kotlin.String)

Accessing Kotlin package-level functions

Currently using Kotlin package-level functions could not be achieved easily. In order to use a package-level function, the class where it's defined should be known. Let's take a look at an example:

var randomNumber = com.example.FunctionsKt.getRandomNumber()

package com.example

fun getRandomNumber() = 42

In the example above, the class FunctionsKt is autogenerated by the Kotlin compiler and its name is based on the name of the file where the functions are defined. Kotlin supports annotating a file to have a user provided name and this simplifies using package-level functions:

var randomNumber = com.example.UtilityFunctions.getRandomNumber()

@file:JvmName("UtilityFunctions")

package com.example

fun getRandomNumber() = 42

Accessing Kotlin extension functions

Currently using Kotlin extension functions could not be achieved easily. In order to use an extension function, the class where it's defined should be known. Also, when invoking it, the first parameter should be an instance of the type for which the function is defined. Let's take a look at an example:

var arrayList = new java.util.ArrayList()

arrayList.add('firstElement')

arrayList.add('secondElement')

com.example.Extensions.switchPlaces(arrayList, 0, 1)

package com.example

import java.util.ArrayList

fun ArrayList<String>.switchPlaces(firstElementIndex: Int, secondElementIndex: Int) {

val temp = this[firstElementIndex]

this[firstElementIndex] = this[secondElementIndex]

this[secondElementIndex] = temp

}

In the example above, the class ExtensionsKt is autogenerated by the Kotlin compiler and its name is based on the name of the file where the functions are defined. Kotlin supports annotating a file to have a user provided name and this simplifies using package-level functions:

var arrayList = new java.util.ArrayList()

arrayList.add('firstElement')

arrayList.add('secondElement')

com.example.ExtensionFunctions.switchPlaces(arrayList, 0, 1)

@file:JvmName("ExtensionFunctions")

package com.example

import java.util.ArrayList

fun ArrayList<String>.switchPlaces(firstElementIndex: Int, secondElementIndex: Int) {

val temp = this[firstElementIndex]

this[firstElementIndex] = this[secondElementIndex]

this[secondElementIndex] = temp

}

Multithreading & Workers

Multithreading Model

One of NativeScript's benefits is that it allows fast and efficient access to all native platform (Android/Objective-C) APIs through JavaScript, without using (de)serialization or reflection. This however comes with a tradeoff - all JavaScript executes on the main thread (AKA the UI thread). That means that operations that potentially take longer can lag the rendering of the UI and make the application look and feel slow.

To tackle issues with slowness where UI sharpness and high performance are critical, developers can use NativeScript's solution to multithreading - worker threads. Workers are scripts executing on a background thread in an absolutely isolated context. Tasks that could take long to execute should be offloaded on to a worker thread.

Workers API in NativeScript is loosely based on the Dedicated Web Workers API and the Web Workers Specification

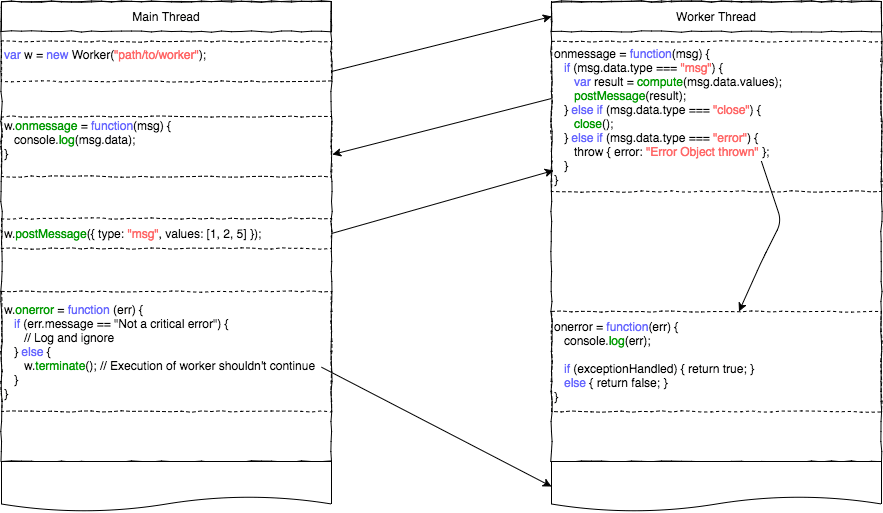

Workers API

Worker Object prototype

new Worker(path)- creates an instance of a Worker and spawns a new OS thread, where the script pointed to by thepathparameter is executed.postMessage(message)- sends a JSON-serializable message to the associated script'sonmessageevent handler.terminate()- terminates the execution of the worker thread on the next run loop tick.

Worker Object event handlers

onmessage(message)- handle incoming messages sent from the associated worker thread. The message object has the following properties:message.data- the message's content, as sent in the worker thread'spostMessage

onerror(error)- handle uncaught errors from the worker thread. The error object exposes the following properties:error.message- the uncaught error, and a stacktrace, if applicableerror.filename- the file where the uncaught error was thrownerror.lineno- the line where the uncaught error was thrown

Worker Global Scope

self- returns a reference to theWorkerGlobalScopeitselfpostMessage(message)- sends a JSON-serializable message to the Worker instance'sonmessageevent handler on the main thread.close()- terminates the execution of the worker thread on the next run loop tick

Worker Global Scope event handlers

onmessage(message)- handle incoming messages sent from the main thread. The message object exposes the following properties:message.data- the message's content, as sent in the main thread'spostMessage

onerror(error)- handle uncaught errors occurring during execution of functions inside the Worker Scope (worker thread). Theerrorparameter contains the uncaught error. If the handler returns a true-like value, the message will not propagate to the Worker instance'sonerrorhandler on the main thread. Afteronerroris called the worker thread, execution is not terminated and the worker is still capable of sending/receiving messages.onclose()- handle any "clean-up" work; suitable for freeing up resources, closing streams and sockets.

Sample Usage

Note

In order to use console's methods, setTimeout/setInterval, or other functionality coming from the core-modules package, the globals module needs to be imported manually to bootstrap the infrastructure on the new worker thread.

main-view-model.js

...

const worker = new Worker("./workers/image-processor");

worker.postMessage({ src: imageSource, mode: 'scale', options: options });

worker.onmessage = function(msg) {

if (msg.data.success) {

// Stop idle animation

// Update Image View

// Terminate worker or send another message

worker.terminate();

} else {

// Stop idle animation

// Display meaningful message

// Terminate worker or send message with different parameters

}

}

worker.onerror = function(err) {

console.log(`An unhandled error occurred in worker: ${err.filename}, line: ${err.lineno} :`);

console.log(err.message);

}

...

workers/image-processor.js

require('@nativescript/core/globals') // necessary to bootstrap ns modules on the new thread

global.onmessage = function (msg) {

const request = msg.data

const src = request.src

const mode = request.mode || 'noop'

const options = request.options

const result = processImage(src, mode, options)

const msg = result !== undefined ? { success: true, src: result } : {}

global.postMessage(msg)

}

function processImage(src, mode, options) {

console.log(options) // will throw an exception if `globals` hasn't been imported before this call

// image processing logic

// save image, retrieve location

// return source to processed image

return updatedImgSrc

}

// does not handle errors with an `onerror` handler

// errors will propagate directly to the main thread Worker instance

// to handle errors implement the global.onerror handler:

// global.onerror = function(err) {}

General Guidelines

For optimal results when using the Workers API, follow these guidelines:

- Always make sure you close the worker threads, using the appropriate API (

terminate()orclose()), when the worker's finished its job. If Worker instances become unreachable in the scope you are working in before you are able to terminate it, you will be able to close it only from inside the worker script itself by calling theclose()function. - Workers are not a general solution for all performance-related problems. Starting a Worker has an overhead of its own, and may sometimes be slower than just processing a quick task. Optimize DB queries, or rethink complex application logic before resorting to workers.

- Since worker threads have access to the entire native SDK, the NativeScript developer must take care of all the synchronization when calling APIs which are not guaranteed to be thread-safe from more than one thread.

Limitations

There are certain limitations to keep in mind when working with workers:

- No JavaScript memory sharing. This means that you can't access a JavaScript value/object from both threads. You can only serialize the object, send it to the other thread and deserialize it there. This is what postMessage() function is responsible for. However, this is not the case with native objects. You can access a native object from more than one thread, without copying it, because the runtime will create a separate JavaScript wrapper object for each thread. Keep in mind that when you are using non-thread-safe native APIs and data you have to handle the synchronization part on your own. The runtime doesn't perform any locking or synchronization logic on native data access and API calls.

- Only JSON-serializable objects can be sent with postMessage() API.

- You can’t send native objects. This means that you can't send native objects with postMessage, because in most of the cases JSON serializing a JavaScript wrapper of a native object results in empty object literal - "{}". On the other side this message will be deserialized to a pure empty JavaScript object. Sending native object is something we want to support in the future, so stay tuned.

- Also, be careful when sending circular objects because their recursive nodes will be stripped on the serialization step.

- No object transferring. If you are a web developer you may be familiar with the ArrayBuffer and MessagePort transferring support in browsers. Currently, in NativeScript there is no such concept as object transferring.

- Currently, you can’t debug scripts running in the context of worker thread. It will be available in the future.

- No nested workers support. We want to hear from the community if this is something we need to support.

Demo projects

The below-attached projects demonstrate, how we could use the multithreading functionality in non-Angular NativeScript project as well as NativeScript Angular one.

Metadata filtering

Metadata

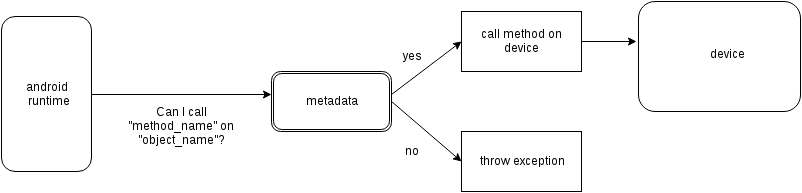

To allow JavaScript code to call into native iOS or Android code both NativeScript runtimes need the so called metadata. It contains all the necessary information about each of the supported native classes, interfaces, protocols, structures, enumerations, functions, variables, etc. and is generated at build time by examining the native libraries from the iOS/Android operating systems' SDKs and any third-party libraries and frameworks that are used by the {N} application. More detailed descriptions about the iOS and Android metadata format and features can be found in these two articles:

Android Metadata

The NativeScript Metadata is the mapping between the JavaScript and the Android world. Besides a full list with all the available classes and methods, the metadata contains the JNI signature for each accessible Android method/field. It is pre-generated, in a binary format, and embedded in the application package (apk), storing the minimal required information thus providing small size and highly efficient read access. The generation process uses bytecode reading to parse all publicly available types in the Android libraries supplied to the NativeScript project. The generator works as part of the Android build process, meaning that no user interaction is required for it to work.

Metadata API Level

Only Android public APIs (including those of any plugins added to the project) present in the metadata will be accessible in JavaScript/TypeScript. That means, if an application is built with metadata for API level 23 (Android Marshmallow 6.0 – 6.0.1), the application user might have problems when running the application on an older device, for example with API levels 17 through 19 (Android KitKat 4.4 – 4.4.4).

Metadata is built automatically for the application. The metadata API level, or simply put, what API level the metadata is built for, is determined by the --compileSdk flag passed to the build. By default the nativescript CLI automatically detects the highest Android API level installed on the developer's machine and passes it to the build implicitly. This --compileSdk flag can be supplied explicitly when starting a build: ns run android --compileSdk=1.

Metadata Limitations

Let's look at the Android TextView. In API level 21 a method called getLetterSpacing was added. What that means is, an application developer can use the "getLetterSpacing` method only on two conditions:

- The built metadata is >= 21

- The device that the application will be running on is >= 21

Possible Implications When Working With Android APIs

Implication A: Building against lower API level.

If an application is built with --compileSdk flag pointing to a lower Android API level, for example 19, the generated metadata will also be for API level 19. In that case making calls to API in Levels 21 and up will not be possible, because the metadata comprises of meta information about API level <= 19.

This problem is easily solved by not specifying a --compileSdk flag and using the default behavior.

Implication B: Building against higher API level.

What happens when an application is built with higher API level(e.g. 23), but runs on a device with a lower API level(e.g. 20)? First the metadata is built for API level 23. If the javascript code calls a method introduced after API level 20 the Android runtime will try to call this method because it will recognize it in the metadata, but when the actual native call is made on the lower level device, an exception will be trown because this method won't be present on the device.

This problem is solved by detecting the API level at run-time and using the available API.

Detecting the API Level in JavaScript:

if (android.os.Build.VERSION.SDK_INT >= 21) {

// your api level-specific code

}

Accessing APIs

One of NativeScript's strongest capabilities is the access to Android (also referred to as 'Java/Kotlin' or 'native') APIs inside JavaScript/TypeScript. That's possible thanks to build-time generated Metadata chunks which hold the information about the public classes from the Android SDK, Android support libraries, and any other Android libraries which may be imported into your Android NativeScript project.

Note

'Android classes' and 'Java/Kotlin classes' are used interchangeably throughout the article to refer to classes in the Java/Kotlin programming language.

Access Android Packages

The Android packages are available in the JavaScript/TypeScript global context and are the entry point for accessing Android APIs. Think of them as of TypeScript/C# namespaces, or the way to access sets of classes. For example, the android.view package grants access to classes like android.view.View - the base of all view elements in Android.

In order to access a particular class in JavaScript/TypeScript the full package name leading up to the class name needs to be specified, or you may end up working with undefined variables.

The above is accessed in JavaScript like:

const javaLangPkg = java.lang

const androidPkg = android

const androidViewPkg = android.view

// access classes from inside the packages later on

const View = androidViewPkg.View

// or

const View = android.view.View

const Object = javaLangPkg.Object // === java.lang.Object;

To find out the package name of an Android class, refer to the Android SDK Reference, or to the supplied API Reference of a plugin, when importing 3rd-party Android components into your project.

For example, if you need to work with the Google API for Google Maps, after following the installation guide, you may need to access packages from the plugin like com.google.android.gms.maps, which you can find a reference for at Google APIs for Android Reference

Note

To have access and Intellisense for the native APIs with NativeScript + TypeScript or NativeScript + Angular projects, you have to add a dev dependency to @nativescript/types. More details about accessing native APIs with TypeScript can be found [here]({% slug access-native-apis %}#intellisense-and-access-to-native-apis-via-typescript).

Note

(Experimental) Alternatively, to get Intellisense for the native APIs based on the available Android Platform SDK and imported Android Support packages (added by default to your Android project), supply the --androidTypings flag with your ns run | build android command. The resulting android.d.ts file can then be used to provide auto-completion.

Note

You cannot use APIs that are not present in the metadata. By default, if --compileSdk argument isn't provided while building, metadata will be built against the latest Android Platform SDK installed on the workstation. See metadata limitations.

Access Android Classes

Classes (See OOP) are the schematics to producing building blocks (Objects) in Android, as such, they are used to represent almost everything you see, as well as what you don't see, in an Android application - the Android layouts are objects built from classes, the buttons and text views also have class representations. Classes in Java and Kotlin have unique identifiers denoted by the full package name (see above), followed by the actual class name (usually capitalized - see above - 'View')

Accessing classes in Android you would normally add an import statement at the beginning of the Java/Kotlin file, to allow referring to the class only by its name. If the developer decides, they may be as expressive as possible by using the full class identifier too:

package my.awesome.application;

import android.view.View;

public class ... {

public static void staticMethod(context) {

View newView = new View(context);

// or

android.view.View newView2 = new android.view.View(context);

}

}

Accessing Android classes, in the JavaScript/TypeScript of a NativeScript application, is kept as close to the original Java syntax as the JavaScript language allows:

function arbitraryFunction(context) {

// 'context' is a JavaScript wrapper (Proxy - see below) for the underlying android.content.Context Java instance

const View = android.view.View

const newView = new View(context)

// or

const newView2 = new android.view.View(context)

// newView and newView2 will be JavaScript wrappers (Proxies - see below) for the created Java android.view.View objects

}

Proxies

The JavaScript objects that lie behind the Android APIs are called Proxies. There are two types of proxies:

Package Proxy

Provides access to the classes, interfaces, constants and enumerations within each package. See java.lang.

Class Proxy

Represents a thin wrapper over a class or an interface and provides access to its methods and fields. From a JavaScript perspective this type of proxy may be considered as a constructor function. For example android.view.View is a class proxy.

The result of the constructor calls (new ...()) will create native android.view.View instances on the Android side and a special hollow Object on the JavaScript side. This special object knows how to invoke methods and access fields on the corresponding native instance. For example we may retrieve the path value of the above created File using the corresponding File class API like:

Access Methods, Fields and Constants

Thanks to the 'proxying' system, Java/Kotlin methods and fields can be accessed through the JavaScript wrappers of the native instances. For example, you may retrieve the result of a method call to the Java instance:

const javaObj = new java.lang.Object()

// result is `int` in Java, marshalled to a JavaScript number

const javaObjHashCode = javaObj.hashCode()

// prints out the hashCode number

console.log(javaObjHashCode)

Public and private members, as well as static fields of an instance, or Java/Kotlin classes can also be accessed. The android.view.View class will be used below:

// retrieve context

const context = ...;

const newView = new android.view.View(context);

// public member call to 'public void clearFocus()' as declared in Android

newView.clearFocus();

// public static field access to 'public static final SCALE_X' as declared in Android

let newViewScaleX = newView.SCALE_X;

// public static field access to `FOCUS_UP` - represents an integer as declared in the Android source

const focusUpDirection = android.view.View.FOCUS_UP;

// public member call to 'public View focusSearch(int direction)'

let foundView = newView.focusSearch(android.view.View.FOCUS_UP);

// static method call to 'public static int generateViewId()' - generates a random integer suitable for Android Views

const randomViewId = android.view.View.generateViewId();

Extend Classes and Interfaces

For a comprehensive guide on extending classes and implementing interfaces through JavaScript/TypeScript check out the dedicated article.

Full-fledged Example

Let's take a sample Android code, and transcribe it to JavaScript/TypeScript.

The following code (courtesy of startandroid.ru) creates an Android layout, and adds a couple Button and TextView elements:

public class MainActivity extends Activity {

/** Called when the activity is first created. */

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

// creating LinearLayout

LinearLayout linLayout = new LinearLayout(this);

// specifying vertical orientation

linLayout.setOrientation(LinearLayout.VERTICAL);

// creating LayoutParams

LayoutParams linLayoutParam = new LayoutParams(

LayoutParams.MATCH_PARENT,

LayoutParams.MATCH_PARENT

);

// set LinearLayout as a root element of the screen

setContentView(linLayout, linLayoutParam);

LayoutParams lpView = new LayoutParams(

LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT,

LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT

);

TextView tv = new TextView(this);

tv.setText("TextView");

tv.setLayoutParams(lpView);

linLayout.addView(tv);

Button btn = new Button(this);

btn.setText("Button");

linLayout.addView(btn, lpView);

LinearLayout.LayoutParams leftMarginParams = new LinearLayout.LayoutParams(

LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT,

LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT

);

leftMarginParams.leftMargin = 50;

Button btn1 = new Button(this);

btn1.setText("Button1");

linLayout.addView(btn1, leftMarginParams);

LinearLayout.LayoutParams rightGravityParams = new LinearLayout.LayoutParams(

LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT,

LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT

);

rightGravityParams.gravity = Gravity.RIGHT;

Button btn2 = new Button(this);

btn2.setText("Button2");

linLayout.addView(btn2, rightGravityParams);

}

}

class MainKotlinActivity: Activity() {